In collaboration with CMTC-OVM, the American National Institute of Health, among others, published an article in the renowned journal ‘American Journal of Medical Genetics’. Thanks to this collaboration, the booklet ‘parents with an unborn child with a possible rare condition’ has also been developed.

Rare diseases (RDs) are defined as diseases that affect a low number of the population. Prenatal diagnoses of RDs can add a lot of unique stress for parents. For example, parents who have prenatal diagnoses experience not only grief of expectation, but are forced to become patient advocates with incomplete information as their child is not yet born, and in many cases parents experience a lot of uncertainty. This typically involves seeking support groups and finding pre and postnatal specialists all which come with mental and financial cost. Here we discuss the importance of targeted patient resources for parents to help alleviate some of their stress. Patient advocacy organizations can be incredibly useful for parents to navigate the complex healthcare system and help mitigate feelings of isolation, especially when parents can talk to others in a similar situation.

We collaborated with a patient organization to create a prenatal parent support guide to address how parental needs such as mental well-being and practicing self-care can be met. We hope that resources such as these can help empower those with a pregnancy affected with a RD diagnosis.

Definition of a rare disease

A disease is defined as rare if it affects a relatively small population of patients. Based on the country, the definition of classifying a disease as rare varies. For instance, in the United States the Orphan Drug Act defines a rare disease based on if less than 200,000 people are affected (96 Stat. 2049) but in the European Union, a disease is rare if less than 1 in 2000 people are affected (“Medicines for rare diseases – orphan drugs,” 1999; “Orphan Drug Act,” 1983). The collective term “rare” disease is quite misleading because they are not all that rare. According to NIH’s Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD), 1 in 10 people in the US are diagnosed with a rare disease (GARD, https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/about). This shockingly high number means that not only is a significant amount of the population diagnosed with a RD, but an even larger number of the population knows and/or cares for a loved one with a RD.

Challenges to parents with newborns with a RD

In general, parents to newborns face challenges including sleep deprivation, managing time between working and caring for the baby, and maintaining their own wellbeing. It is estimated that up to 9.3% mothers and up to 4.0% fathers may experience post-partum depression (PPD), and in up to 3.18% couples PPD may occur in both parents simultaneously (Escribà-Agüir & Artazcoz, 2011; Smythe et al., 2022). However, when a diagnosis of a RD is added on top of having a newborn, it can have a drastic change in the parent’s stress (Dempsey et al., 2021). In many cases, obstetricians and pediatricians are not equipped to dealing with RDs due to a lack of knowledge or equipment. This means that parents must go to specialists, and depending on the disease, specialists may also be scarce. This proves to be difficult for families living in remote locations especially when specialists are located solely in cities (Long et al., 2022). In one study of patients seen by telemedicine or in person by Clinical Pediatric Genetics at a tertiary care center, the mean distance (as the crow flies) from the patient’s home to hospital was 126 km with a standard deviation of 323 km (Szigety et al., 2022).

Support from medical staff is vital

It is important to discuss how we as researchers and clinicians can do better when seeing children with a RD. To try to understand what resources would be beneficial for patient families, we looked to our patients: “As a parent going through a very challenging time, both emotionally and physically, we knew we would have to eventually move and change our lives for our son’s special care pre- and post-natally. It was extremely helpful to have a proactive team of people working alongside me and my husband. Our clinicians were able to give us the right resources and advice which showed us that they were truly looking out for us and our son, who had a very rare disorder that began in my womb.

The medical staff shared with us resources which we never knew existed and helped us connect with other parents within the hospital for support. My husband and I realized something after we lost our son: support can come from all angles—from family to clinicians. The many specialists we met with helped us get through one of the hardest situations we would ever face. Without this support from the hospital, the outcome can be devastating and look grim and very discouraging. We are thankful to have had such an amazing team—they were open to hearing all our concerns and answered all our questions. Without a doubt, the parent resources that were shared with us made the biggest difference.”

Patient Advocacy Organizations

Patient Advocacy Organizations (PAO) are an indispensable resource for parental emotional support during their journey. Patients and parents often report feelings of isolation, especially in cases where their child may be affected by an extremely RD (Baumbusch et al., 2019; Long et al., 2022). These organizations can help families connect with one another to talk about shared experiences and provide resources about the medical condition both for families and practioners not familiar with the RD, psychosocial supports, and information for siblings. Cutis Marmorata Telangiectatica Congenita and Other Vascular Malformations (CMTC-OVM) is a PAO for individuals with vascular malformations which has developed parent support guides in multiple languages based on age to assist in caring for a child with a rare condition (https://www.cmtc.nl/en/activities/information-folders/parents-support-guide/, (CMTC-OVM, 2022). However, a prenatal guide, which would be focused on parental health, was lacking.

Patient support guide

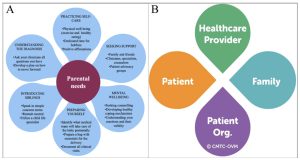

In response to our patient’s comments and in collaboration with CMTC-OVM we developed a patient support guide for parents who have received a fetal diagnosis. Previous work identified the emotional, practical, physical, psychological, informational, and social needs of parents who have a child with a RD (Pelentsov et al., 2015). In the Prenatal Parent Support Guide, we address these parental needs and summarize different strategies of how to meet these parental needs (Figure 1A). For instance, we talk about the importance of parents seeking self-care which includes exercising and making time for hobbies that the parents previously enjoyed doing. Part of self-care includes the often-overlooked mental wellbeing: parents should seek counselling early on to help them learn ways to cope. Another important component is ways that parents can seek support. Parents should seek support from family, members of their clinical team and PAOs.

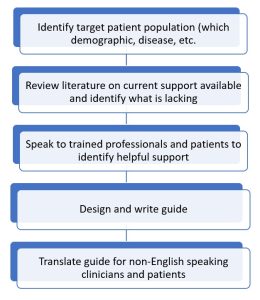

While CMTC-OVM is primarily for patients with vascular malformations, this guide we have created is generalizable for patients with any rare disease. There are many shared experiences that parents face between all RDs such as navigating the healthcare system, experiencing stress and anxiety, and having difficulties maintaining a healthy lifestyle. We thought it best to make this a highly collaborative project including a PAO, genetic counselor, clinical geneticist, and most importantly, a patient-parent. By having this diverse group of experts, we collectively addressed concerns faced by a parent firsthand. It is invaluable having a PAO as part of this project because they are often the party most easily accessible to patients and families. So if a group looking to create a similar support guide has a certain disease in mind, their guide can directly benefit patients affected by said disease when a PAO is involved. Our final step was to get the support guide translated into multiple languages because we wanted to ensure that non-English speaking patients and clinicians are able to take advantage of the guide as well. We have summarized the steps we have taken to plan and write the support guide.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________

As depicted in our patient’s story regarding her son, supportive care can be incredibly useful and even essential in a family’s journey with a RD, especially when navigating a complex healthcare environment. This demonstrates the importance of collaborative care between healthcare providers, PAOs, and most importantly the patients and their families (Figure 1B). We hope that resources such as the parent support guide we have created and resources from other groups can come together to lessen the burden that families face and aid in meeting the parental needs that families have.

Author Contributions

DPS, JOC, and SES wrote the original draft. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Authors

Dhyanam P. Shukla (1,) Jennifer Ortiz Cutshall (2,) Lex van der Heijden (3,) Erica Schindewolf (4), Sarah E. Sheppard (1)

Affiliations

1 Unit on Vascular Malformations, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD, USA

2 York, PA, USA

3 CMTC-OVM, Netherlands

4 Richard D. Wood Jr. Center for Fetal Diagnosis and Treatment, The Children’s Hospital of

Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA, USA

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under award number HD009003-01 (SES). The content is solely the

responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official 26 views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

Baumbusch, J., Mayer, S., & Sloan-Yip, I. (2019). A 138 lone in a Crowd? Parents of Children with Rare Diseases’ Experiences of Navigating the Healthcare System. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 28(1), 80-90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-018-0294-9

CMTC-OVM, N. G. (2022). Parents Support Guide. CMTC-OVM. Retrieved 24 May from

https://www.cmtc.nl/en/activities/information-folders/parents-support-guide/

Dempsey, A. G., Chavis, L., Willis, T., Zuk, J., & Cole, J. C. M. (2021). Addressing Perinatal

Mental Health Risk within a Fetal Care Center. J Clin Psychol Med Settings, 28(1), 125-

136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-020-09728-2

Escribà-Agüir, V., & Artazcoz, L. (2011). Gender differences in postpartum depression: a

longitudinal cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health, 65(4), 320-326.

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2008.085894

https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/about, G.-. What Is a Rare Disease? Genetic and Rare Diseases

Information Center. Retrieved 24 May from https://rarediseases.info.nih.gov/about

Long, J. C., Best, S., Easpaig, B. N. G., Hatem, S., Fehlberg, Z., Christodoulou, J., &

Braithwaite, J. (2022). Needs of people with rare diseases that can be supported by

electronic resources: a scoping review. BMJ Open, 12(9), e060394. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060394

Medicines for rare diseases – orphan drugs, Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 (1999).

Orphan Drug Act, Pub. L. No. 97-414, 96 2049-2066 (1983).

Pelentsov, L. J., Laws, T. A., & Esterman, A. J. (2015). The supportive care needs of parents

caring for a child with a rare disease: A scoping review. Disability and Health Journal, 8(4), 475-491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.03.009

Smythe, K. L., Petersen, I., & Schartau, P. (2022). Prevalence 160 of Perinatal Depression and Anxiety in Both Parents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open,

5(6), e2218969-e2218969. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.18969

Szigety, K. M., Crowley, T. B., Gaiser, K. B., Chen, E. Y., Priestley, J. R. C., Williams, L. S.,

Rangu, S. A., Wright, C. M., Adusumalli, P., Ahrens-Nicklas, R. C., Calderon, B., Cuddapah, S. R., Edmondson, A., Ficicioglu, C., Ganetzky, R., Kalish, J. M., Krantz, I. D., McDonald-McGinn, D. M., Medne, L., . . . Sheppard, S. E. (2022). ClinicalEffectiveness of Telemedicine-Based Pediatric Genetics Care. Pediatrics, 150(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-054520